다발경화증의 진행과 예후 예측인자: 임상적-영상적 측면

Clinicoradiological Factors for Predicting and Monitoring the Progression of Multiple Sclerosis

Article information

Trans Abstract

As knowledge of pathophysiology and treatment options for multiple sclerosis has been expanding, decisions about when and which drugs we should start and switch appropriately have became important. It should be based upon individuals’ baseline clinical, environmental, demographical, and radiological biomarkers that correlate with long-term disability. In addition, a timely assessment of treatment response and adverse effect should be followed after the initial treatment. Several prognostication tools were developed and large longitudinal studies validated them. They consisted of composition of demographical factors, clinical relapse rate, relapse severity, involvement of specific functional system, magnetic resonance imaging activity and characteristic findings (gadolinium enhancement, brain atrophy, and paramagnetic rim lesion, etc.).

서론

다발경화증(multiple sclerosis, MS)은 재발과 완화를 반복하거나 점진적으로 진행하는 경과를 특징으로 하는 중추신경계의 만성 자가면역성 염증성 탈수초질환으로 재발이 자주 반복될 경우 완전히 호전되지 않고 신경학적 장애가 누적된다.1 여러 가지 종단 추적 연구를 통하여 임상단독증후군(clinically isolated syndrome, CIS) 발생 시점부터 인터페론(interferon), glatiramer acetate와 같은 질병조절 치료제(disease modifying drug, DMT)를 조기에 시작할 경우 재발 완화와 신경학적 장애축적을 예방하는 데 중요하다고 밝혀졌다.2-4 근래에는 MS의 신경면역 기전 및 병태생리에 대한 지식 향상을 바탕으로 다양한 질병조절 치료제가 새롭게 개발되었고 임상진료 현장에서 쓰이고 있다.5 또한 초기 DMT로서 인터페론과 같은 중등도 효능(moderate efficacy) 약제 위주로 시작하는 전통적인 치료 전략의 패러다임 전환을 제시할 만한 연구 결과도 발표되고 있다.6,7 이에 수반하여 MS 진단 후 초기 치료를 시작할 때 환자 개개인의 특성과 예후 예측인자를 고려한 약제 선택과 치료 시작 후 주기적인 치료 반응 평가가 중요해지고 있다.

본론

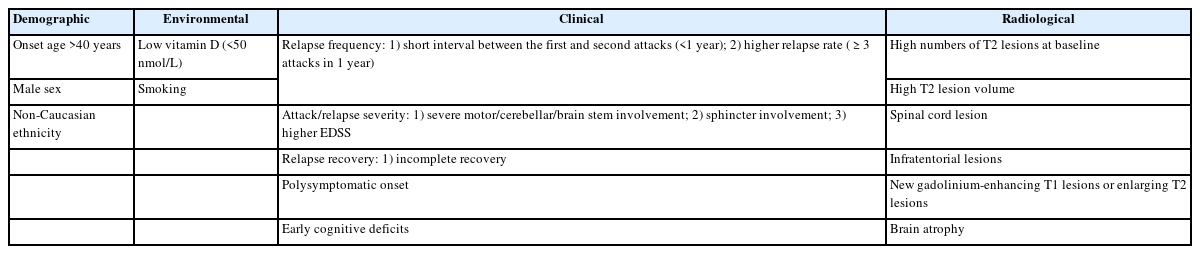

인구학 및 환경적 측면에서의 예후 예측요인

MS가 발병한 개인의 성별, 인종/민족, 발병 시점의 연령은 고정불변하는 내재적 요인이며 질병 경과에 영향을 줄 수 있다고 알려져 있다. MS에 이환되는 환자의 성비는 여성 대 남성이 1.5 대 1에서 2.5대 1 사이로 여성에서 높게 보고되지만, 발병 후 장애 이정표(disability milestone)까지 도달하는 데 걸리는 시간과 장애진행 속도는 남성에서 더 빠르게 보고되었다.8,9 Kurtzke 장애상태척도(Kurtzke disability status scale) 4점-완전한 정상은 아니지만 도움 없이 독립 보행이 가능한 수준-까지 도달하는 데 소요되는 기간의 중앙값이 남성에서 여성보다 2.4년 빨랐고 6점과 7점까지 도달하는 속도는 5.9년, 5.3년 차이로 남성에서 더욱 빨라졌다.8

MS는 20-40세 사이에 가장 호발하며, 첫 발병 시 나이가 많을수록 빠른 장애진행 속도를 보인다고 알려져 있다.8 일차 진행형 MS (primary progressive MS) 및 성별과 무관하게 늦은 발병 연령은 장애진행의 예후 예측인자였으며10 많은 나이에 대한 기준은 40세 초과 또는 50세 이상으로 보고 있다.8,10,11

MS 발생률 및 유병률은 북미, 오스트레일리아 남부, 뉴질랜드 지역에 거주하는 백인에게 높지만 장애진행 속도는 아프리카계 또는 히스패닉계 미국인 같은 비유럽 민족의 환자에게서 더 빠르다는 보고가 있다.12

환경적 측면에서의 예후 예측요인으로는 대표적으로 흡연과 비타민 D를 고려할 수 있다. 흡연의 경우 비흡연자에 비하여 MS 발병의 시작, CIS에서 MS로, 재발완화형 MS (relapsing-remitting MS)에서 이차진행형 MS (secondary progressive MS, SPMS)로의 진행에 모두 영향을 미친다.13 따라서 MS가 확진된 환자가 흡연자일 경우에는 반드시 금연하도록 권고한다.4

비타민 D 역시 MS 발병의 시작과 진행에 영향을 미친다고 여겨진다. 북반구와 남반구의 위도가 높은 지역으로 갈수록 MS 유병률이 높아지는 것은 자외선 노출과 관련이 있으며 이는 곧 비타민 D와 관련된다. 미국의 대규모 간호사건강연구(Nurses’ Health Study) 코호트를 분석한 결과 규칙적으로 비타민 D 보충제를 섭취한 군(매일 400 IU 이상)이 그렇지 않은 군에 비해 MS 발병 상대 위험비가 40% 낮았다.14 혈청 25-히드록시비타민 D(25(OH)D) 수치는 질병 활성도와 관련이 있는 것으로 연구 보고가 되었는데 25(OH)D 혈청 수치가 높을수록 임상적 재발 위험이 낮고 MRI에서 새로운 T2 병변이나 조영증강 병변도 적었다.15,16 혈청 농도를 20 ng/mL (50 nmol/L) 높일 경우 재발 위험이 50% 낮아졌다. 비타민 D 섭취가 비교적 저렴하고 안전한 중재인 점에서 MS 환자에게 고려할 만하며, 권장용량이나 혈청 농도에 대해서 명확한 가이드라인은 없지만, 최대 일일 4,000 IU 이내로 복용하는 것과 혈청 농도 30 ng/mL (75 nmol/L) 이상 유지하는 것이 권고된다.11,17

임상적 측면에서의 예후 예측요인

MS 발병 초기에 임상적 재발이 잦거나(첫 2년 내에 3회 이상) CIS 발현 후 첫 재발(두 번째 급성 증상) 간에 시간 간격이 1년 미만으로 짧은 경우 장애상태척도(extended disability status scale, EDSS) 6점-보행 시 도움이 필요하고 혼자 걷지 못하는 수준-까지 장애가 더 빠르게 진행한다고 알려져 있다.18 한 연구는 발병 2년 내 급성 증상이 한 번인 환자에 비해 3번 이상 발생한 환자가 7.6년 빠르게 EDSS 6점에 도달하지만 2년 이후의 재발 빈도나 총 재발 횟수는 유의미한 예측인자가 아니라고 보고하였다.18 반면 다른 연구는 발병 후 5년까지도 재발 빈도가 잦을수록 비가역적인 장애축적과 장기적인 예후가 나쁠 수 있다고 보고하고 있다.19

급성기 병변이 심한 신경학적 증상을 보이거나 보행장애나 괄약근 기능장애를 일으키거나, 질병 초기에 치료에도 불구하고 회복이 불완전하여 후유 증상이 남을 경우에도 더 빠른 EDSS 점수 악화를 보일 수 있다.9,20 원심성 신경섬유(efferent tract)를 주로 침범하여 근력 약화와 보행장애가 생긴 경우는 구심성 신경섬유(afferent tract)를 주로 침범한 경우보다 불량한 예후를 보인다.9,19 예를 들어 MS 탈수초 병변이 척수염으로 나타나더라도 순수 감각신경로보다 피질척수로 위주의 병변이 있거나 심한 배뇨/배변장애를 동반한 경우가 해당되겠다. 첫 번째 증상(CIS) 또는 첫 번째 재발에서 회복 정도가 불완전할 경우 장애축적 및 진행 속도에 나쁜 영향을 미치는 점은 비교적 일관되게 보고된다.8,9,21 급성기 증상 1년 후 EDSS 점수가 2점 미만으로 잘 회복된 경우 10년 후에도 EDSS 3점 미만일 가능성을 시사하는 연구도 있다.22 병변의 위치(localization)도 예후와 관련성을 보일 수 있는데 CIS 발현 시 괄약근 기능장애를 보이는 경우는 재발 및 장애척도 진행 같은 불리한 예후와 강한 연관성이 있는 반면, CIS 발현 시 시신경염을 보이는 경우는 유리한 예후와 연관성이 있었다.8,9,23 병변 위치 중 운동/소뇌/뇌줄기 기능장애를 보이는 경우는 장애 진행과 관련하여 불리한 예후를 보이는 경향성을 보였으나 그렇지 않은 연구도 있어서 혼재된 결과를 보였다.8,9,18 신경해부학적으로 여러 위치에 동시 발현하는 경우도 장애진행 예측에 있어서는 혼재된 결과를 보였다.

인지기능장애는 축삭신경세포 변성(axonal neurodegeneration)과 뇌 위축(brain atrophy)을 반영하는 기능장애로서 MS 장기적인 예후인자일 가능성이 제시되었으며24 환자의 삶의 질 저하와 직업생활을 어렵게 하는 중요한 원인인데 반해 통상적으로 사용하는 장애진행척도인 EDSS 항목을 통해서는 상세한 평가가 어려운 점이 있다. 따라서 최근에는 별도의 신경심리 검사항목을 통해 MS 환자의 인지처리속도(cognitive processing speed)를 평가하고 치료 효과 판정 항목에도 추가되고 있다.25,26

자기공명영상(MRI) 측면에서의 예후 예측요인

MS 진단 및 치료 방침 결정에 있어서 MRI의 중요성은 이미 잘 알려져 있다. 최초 증상 발생 시점 MRI의 T2 강조영상 고신호 강도의 개수(number), MS-특이적인 위치(뇌실주위, 피질곁, 천막하, 척수), 조영증강 여부는 특히 CIS에서 임상확진 MS (clinically definite MS, CDMS)로의 진행 위험성을 높은 확률로 알려주며 맥도널드 진단 기준에 포함되어 있다.23,27,28 CDMS 진행뿐만 아니라 장애축적과 이차진행형 MS로의 전환 가능성도 높인다고 보고되었는데, 기저(baseline) T2 병변 개수가 10개 이상일 경우는 0개일 경우에 비해 EDSS 3점 도달 위험도가 거의 3배 높게 보고되었고, T2 병변 개수가 성별, 연령, CIS 임상 증상, 질병조절 치료 유무보다 훨씬 통계적으로 유의한 영향력을 보였다.23 한 연구는 시신경염이 첫 증상이었던 MS 환자를 6년간 추적 관찰한 결과, 추적검사에서의 새로운 T2 병변 유무, 새로운 조영증강 병변 유무, 기저 조영증강 병변, 기저 T2 병변 개수, 기저 T2 병변 부피(volume)의 순서로 장애축적과 유의한 상관관계를 확인하였다.29 또한 CIS 시기에 척수(spinal cord) 병변, 천막하(infratentorial) 병변이 있는 경우도 CDMS 진행뿐만 아니라 장애진행과 유의한 상관관계를 보였다.29-31 질병 초기(발병 1-2년 이내) 뇌 위축(brain atrophy) 진행 정도 역시 장기적인 EDSS 악화와 장애축적의 예측인자로 여러 연구에서 보고되고 있으며32,33 최근 중요하게 여겨지는 MS에서의 인지기능저하 및 기분장애와 연관되어 있기도 하다.34 하지만 뇌 위축의 정량적 측정은 현재의 통상적인 MRI 검사로는 시도하기 어려운 제한점이 있다(Table 1).

발병 시점의 임상 정보를 토대로 예후 예측하기

앞에서 살펴본 인구학적, 임상적 예후 예측인자를 토대로 환자 개개인의 장애진행을 예측하기 위한 방법이 고안되었다.35,36 그중 bayesian risk estimate for MS at onset는 베이즈(Bayesian) 모델을 이용하여 발병 시점에 확인할 수 있는 연령, 성별, 임상 증상(예를 들어 괄약근기능, 순수운동기능, 운동-감각기능), 침범한 신경계기능 개수 등에 특정 가중치를 두어 상대적 위험도를 계산(Supplementary Table 1)한 것으로 10년 이내 이차진행형 MS로 진행할 위험이 높고 낮음을 추정할 수 있다. 점수가 삼분위수에 해당하는 0.52보다 높으면 SPMS로 진행 위험도가 높고 일분위수에 해당하는 -0.58보다 낮으면 SPMS로 위험도가 낮다고 본다.37 이를 DMT 종류 결정이나 임상시험 대상자군 선정에 활용할 수 있겠다.

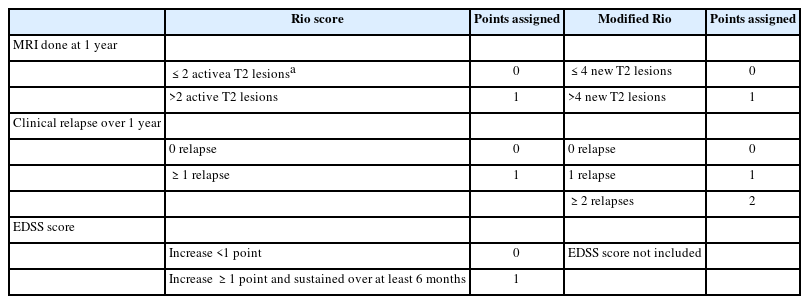

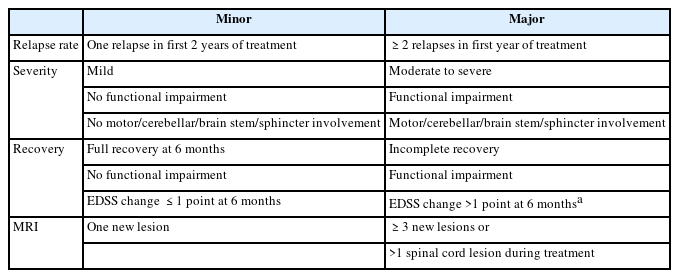

초치료 시작 후 치료 효과 판정

DMT를 쓰기 시작한 이후에는 MS 질병 활성도가 잘 조절되고 있는지 정기적인 평가가 중요하다. 치료실패(treatment failure) 또는 최적하반응(suboptimal response)으로 판단될 경우, 이차진행형 MS로의 전환과 장애진행/축적을 예방하기 위해 DMT 변경이 필요하기 때문이다. 치료 효과 평가에 대해서는 여러 가지 알고리즘이 있지만 본고에서는 Rio score, modified Rio score (Table 2)와 Canada MS working group 치료최적화 권고안(canadian MS working group treatment optimization recommendations) (Table 3)에 대해서 주로 살펴보겠다. Rio score는 치료 시작 1년차에 평가하며 1년에 1회 이상 재발, 6개월에 1점 이상 EDSS 점수 증가, T2 강조 영상과 조영증강 영상에서 3개 이상의 새로운 활동성 병변이 있는 것을 기준으로 삼았으며38 modified Rio score에서는 EDSS 점수 항목을 제외하고 임상적 재발과 MRI 활동성만 고려하였다.39 두 가지 평가 모두 2점 이상일 경우 최적하반응으로 판단하고 DMT 종류 변경을 권고한다. 그러한 이유는 2점 이상인 경우 0, 1점인 경우에 비하여 3-4년 후 장애진행 위험도가 약 2배, 3배 높아지기 때문이다.39 Canada MS working group 권고안은 치료 시작 2년 이내에 임상적 재발, 중증도, MRI 활동성을 평가하며 major 기준을 한 항목이라도 만족할 경우 DMT 종류를 변경하도록 제시하고 있다.11 본고에서 언급한 치료 효과 평가 권고안은 주로 인터페론 같은 경도-중등도(mild-to-moderate) 효능 약제 사용 시 적용되며, 핑골리모드(fingolimod), 나탈리주맙(natalizumab), 클라드리빈(cladribine) 같은 고효능 약제의 임상시험에서는 질병무활성증거(no evidence of disease activity, NEDA)를 효과 평가의 한 척도로 사용하였다.40-42 그러나 장애축적과 같은 장기적인 예후 예측 평가 도구로서의 NEDA는 아직 검정(validation)이 더 필요하다. 한 가지 유념할 점은 초기 치료 반응과 효과 평가 시, DMT 효과가 충분히 나타나는 시기까지 기다려야 한다는 점이다. 통상적인 약제 효과 발현 시기는 나탈리주맙의 경우 최소 1개월, 인터페론, 테리플루노마이드(teriflunomide), 디메틸푸마레이트(dimethyl fumarate), 핑골리모드, 오크레리주맙(ocrelizumab)은 3개월, glatiramer acetate는 6개월, 클라드리빈과 알렘투주맙(alemtuzumab)은 2차년도 투약 이후 18-24개월로 본다.11

결론

빠른 질병조절 치료 시작과 치료 효과에 따른 적절한 약제 변경이 장기적인 MS 환자의 예후에 매우 중요하다. 치료제의 효과가 높아지고 종류도 다양해지면서 과거의 일률적 치료 적용이 아닌, 위험-이익 평가와 개개인의 예후 예측인자 평가를 통한 개인별 맞춤 치료(personalized treatment)의 중요성이 대두되고 있다. MS 환자를 진료하는 신경과 의사에게 인구학적, 임상적, 영상 기반의 예후인자와 그리고 본문에서 다루지는 않았지만 신경 축삭 조직의 손상을 잘 반영하고 MS 질병 활성도 및 장애진행 상태와 높은 상관성을 보이는 바이오마커인 neurofilament light chain43이나 glial fibrillary acid protein44 같은 실험실 기반의 예후인자에 대한 폭넓은 지식이 필요한 이유일 것이다. 이러한 지식을 통합하여 최적의 치료 결정을 내림으로써 궁극적으로 환자의 경과와 장기적인 상태를 개선할 수 있을 것이다.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1.

Calculation of BREMSO (bayesian risk estimate for ms at onset)