대상포진-유발성 항아쿠아포린-4 항체 양성 시신경척수염범주질환: 증례 보고 및 문헌 고찰

Aquaporin-4 Antibody-Positive Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder Triggered by Herpes Zoster: A Case Report and Literature Review

Article information

Trans Abstract

We report the case of a 70-year-old female who developed acute transverse myelitis 1 month after herpes zoster infection and was diagnosed with aquaporin-4 (AQP4) antibody-positive neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. The patient was treated with high-dose corticosteroid and intravenous immunoglobulin therapy and her serum AQP4 antibody seroconverted to negative 3 months later. This case suggests that varicella-zoster virus reactivation may trigger transient AQP4 autoimmunity and highlights the clinical significance of post-treatment seroreversion in distinguishing infection-triggered from idiopathic neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder.

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) is an autoimmune inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS), which primarily affects the optic nerves and spinal cord, causing devastating neurological sequelae.1 The pathophysiology of NMOSD centers around autoantibodies (aquaporin-4 immunoglobulin G, AQP4-IgG) against a water channel on astrocytes. 1 The pathogenesis of NMOSD is thought to involve both genetic predisposition and environmental factors acting in combination.2 In particular, a viral trigger hypothesis suggesting that various viral and bacterial infections can act as trigger factors for the onset or relapse of NMOSD has been proposed.3

Among these infectious agents, rare cases of herpes zoster (HZ), caused by the reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV), associated with the onset of NMOSD have been reported, and a temporal relationship of 2 days to 4 weeks between disease manifestations has been observed.2 Myelitis occurring after VZV infection requires differential diagnosis between two main mechanisms: VZV myelopathy, caused by direct viral invasion, and NMOSD, which occurs as a post-infectious immune-mediated response.2 This is a clinical differentiation, as the therapeutic approach and long-term prognosis differ.1,2 However, the specific mechanism of how VZV reactivation induces AQP4 antibody production and triggers an autoimmune response remains unclear.2 Furthermore, little is known about changes in AQP4 antibodies following the course of treatment in patients with VZV-associated NMOSD, especially the clinical significance of seroconversion from antibody-positive to -negative.4 We report a VZV-triggered AQP4+ NMOSD case with early post-treatment seroreversion.

CASE

A 70-year-old female patient presented with a progressive arm sensory disturbance and severe bilateral leg weakness. Her medical history was notable for an asymptomatic right planum sphenoidale meningioma and chronic hepatitis B, for which she was taking antiviral medication. She had no other comorbidities. Four months before admission, she developed HZ on her right shoulder and neck, was treated with antiviral therapy. After a month, she experienced progressive fatigue, weakness, and hypesthesia in her right arm and shoulder, which spread to left arms. This was accompanied by stiffness and tonic spasms of both hands. Three months later, her weakness in both legs progressed rapidly.

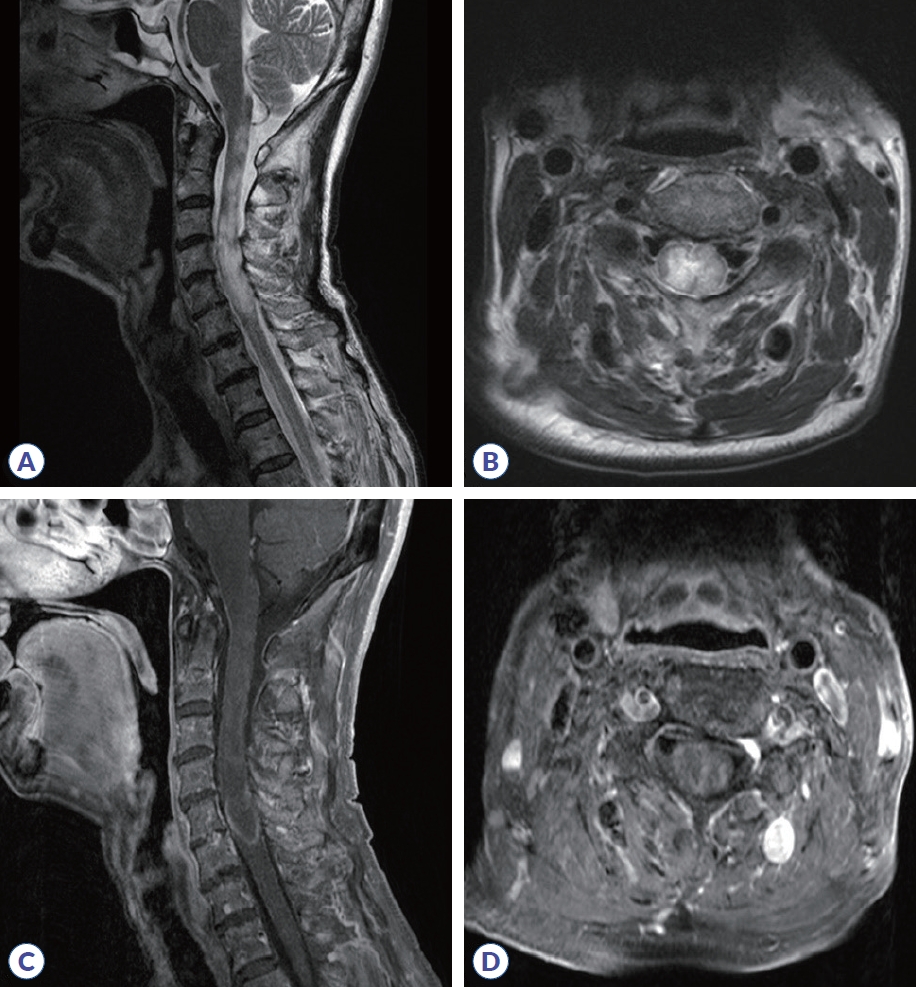

On admission, neurological examination showed normal alertness, language, and cranial nerve function. Sensory testing revealed hypesthesia involving all modalities below the C4 level, accompanied by right arm weakness (medical research council scale [MRC] 4/5-), and bilateral leg weakness (MRC 3/3), resulting in an expanded disability status scale (EDSS) score of 7.0. Deep tendon reflexes were brisk (+++) in the legs, with negative Babinski sign. Positive Lhermitte’s sign and truncal ataxia were present. While motor evoked potentials were normal, abnormal somatosensory evoked potentials in all limbs indicated a central sensory pathway deficit and electromyography suggested concurrent right brachial plexopathy. This suggests that sensory ataxia caused balance impairment and confounded clinical assessment of weakness. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed 7 white blood cell count/μL (88% lymphocytes), protein 51 mg/dL (normal 8-43), and glucose 56.7 mg/dL (CSF/serum ratio 0.36). CSF VZV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was negative, and the CSF FilmArray meningitis/encephalitis panel (Bio-Fire Diagnostics, Salt Lake City, UT, USA) meningitis/encephalitis panel was also negative. Following the prior clinical HZ diagnosis, CSF VZV IgG/immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody titers were not obtained. Spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed cord swelling and T2 high-signal intensity from the C1-C6 level with inhomogeneous enhancement, consistent with longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis (LETM) (Fig. 1). Brain MRI was unremarkable aside from the known meningioma. Serologic testing revealed antinuclear antibody with a mitochondrial pattern at a titer of 1:160. All other tests were negative, including rheumatoid factor, anti-double-stranded DNA, antiphospholipid antibodies (including anticardiolipin IgG/IgM), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody, and the paraneoplastic antibody panel. Anti-SS-A was borderline and anti-SS-B was negative. Cell-based assay (CBA) revealed a positive anti-AQP4 antibody (4+). Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with AQP4-positive NMOSD.

Cervical spinal MRI. (A) Sagittal T2-weighted imaging shows diffuse cord swelling and hyperintensity extending from the cervicomedullary junction to the C6 level. (B) Axial T2-weighted imaging of the upper cervical level shows bilateral hyperintensity, more pronounced on the right. (C) Sagittal post-contrast T1-weighted imaging reveals patchy intramedullary enhancement in the cervical cord. (D) Axial post-contrast T1-weighted imaging shows inhomogeneous enhancement at the mid-cervical level. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

The patient received high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone (1 g/day for 5 days) initially, but since there was no clinical improvement and weakness worsened slightly, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) was subsequently administered for 5 days. Azathioprine (100 mg/day) was started for maintenance, with gabapentin and baclofen for symptom control. Her hypesthesia, ataxia, tonic spasms, and leg weakness partially improved (MRC 4/4). Serum anti-AQP4 antibody seroconverted to negative at 3 months and remained negative at the 7-month follow-up. Eight months post-hospitalization, due to hepatotoxicity and encephalopathy associated with chronic hepatitis B-related liver cirrhosis, azathioprine was discontinued, and maintenance therapy was switched to low-dose oral prednisolone. At the 1-year follow-up, her strength was maintained (MRC 4/5), but she remained wheelchair-dependent due to balance impairment, with an EDSS score of 6.0.

DISCUSSION

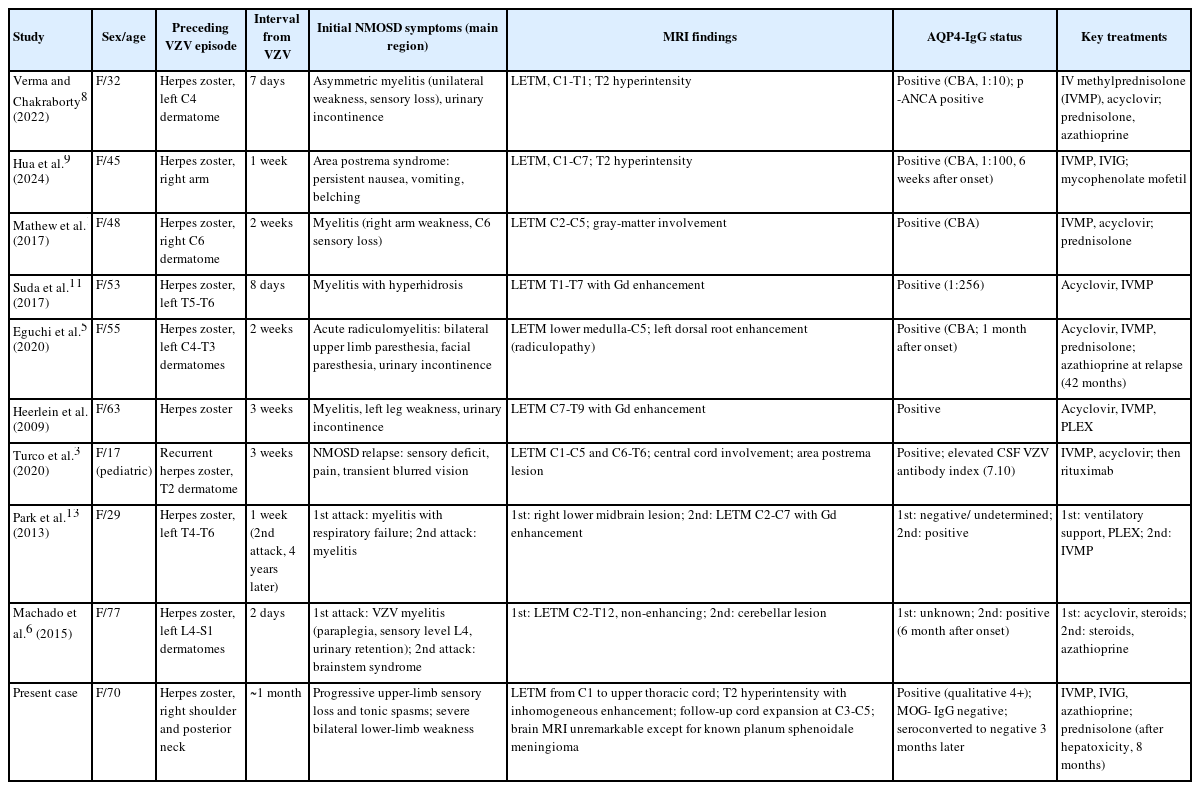

This case presented a diagnostic challenge in differentiating VZV myelopathy from VZV-triggered NMOSD, as both can manifest as LETM.5 However, VZV myelopathy is typically diagnosed based on positive CSF VZV PCR or antibody indices, whereas VZV-triggered NMOSD often presents with negative CSF VZV PCR,2 as in our patient. Given our patient's findings of AQP4 seropositivity, negative CSF VZV PCR, and LETM predominantly affecting the right hemicord correlating with preceding right-sided zoster and concurrent brachial plexopathy, the diagnosis aligned with VZV-triggered NMOSD. To better understand this clinical context, we reviewed nine individual case reports (Table 1). All nine reported VZV-associated cases involved female patients, which is notable even in a female-predominant condition.2 Furthermore, the initial manifestation in all nine cases was LETM rather than optic neuritis, suggesting a potential tendency for VZV reactivation to involve the spinal cord. In some cases, the AQP4 antibody was negative at the initial onset of VZV-associated myelitis but was confirmed to be positive at a later relapse.2,6 These reports suggest that without testing, cases might be misdiagnosed with post-herpetic myelitis. However, subsequent seroreversion was not investigated in any of these nine reviewed VZV-associated NMOSD cases.

Reported cases in which herpes zoster (VZV reactivation) preceded or possibly triggered AQP4-IgG positivity

A distinct aspect of the present case is seroreversion of the AQP4 antibody from positive to negative. AQP4 antibody seroreversion is a reported phenomenon in NMOSD.4 Studies report seroreversion in approximately 11% to 25.7% of initially positive idiopathic NMOSD patients. 4,6 While seroreversion is associated with low initial titer, younger age,4 male sex,6 and treatment with B-cell depleting therapy,5 our patient presented atypically as an elderly, high-titer female treated with azathioprine.

Seroreversion in this patient aligns with a hypothesis where VZV reactivation triggers transient autoimmunity via acute inflammation and subsequent blood-brain barrier disruption, temporarily allowing CNS access to AQP4-reactive B cells or antibodies.7 High-dose intravenous methylprednisolone is presumed to have suppressed this acute inflammation and reduced blood-brain barrier permeability, while IVIG may have provided broader immunomodulation.1 Antibody production was primarily driven by short-lived plasma cells4 activated during acute VZV-induced inflammatory activation; therefore, the resolution of this trigger combined with effective acute therapy could explain subsequent antibody disappearance. This potential mechanism differs from idiopathic NMOSD, where chronic autoimmunity, possibly driven by long-lived plasma cells, is often presumed, making seroreversion less frequent without therapies targeting B cells.4

While reports on VZV-triggered NMOSD are limited and lack data on long-term seropositivity,2 the long-term immunosuppressive treatment for idiopathic NMOSD may not universally apply to cases with a clear, transient infectious trigger and subsequent seroreversion. Consecutive negative results at 3 months and 7 months counterbalance the limitations of fixed CBA, making false negatives unlikely. However, seroreversion does not necessarily imply remission; 50% of seroreverted patients were reported to become seropositive again on follow-up testing, and clinical attacks have occurred during seronegative periods.4 This distinction is critical when weighing the risks of relapse against long-term immunosuppression, especially in patients with comorbidities, such as the hepatotoxicity seen in this case. Further studies are warranted to clarify the long-term prognosis and management of VZV-associated NMOSD in cases demonstrating seroreversion.

Notes

Acknowledgements

DM acknowledges financial support from the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) through a graduate scholarship program.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: DM, SIO. Data curation: all authors. Visualization: DM, SIO. Methodology: DM, SIO. Project administration: DM, SIO. Writing-original draft: DM, SIO. Writing-review & editing: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Funding Statement

None.

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.

Ethical Approval

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kyung Hee University Hospital.

Patient Consent for Publication

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication.